Transport Planning in the UK: Part 1 A Refresh, Organisations, Infrastructure, Policy, and Housing

I thought I’d pick up another light topic that has been sat in my blog backlog. This is the first in a series so stay tuned….

I thought I’d pick up another light topic that has been sat in my blog backlog. This is the first in a series so stay tuned….

I’ve been doing quite a lot of work around transport recently and am leading this area in our Place and Infrastructure cluster here at TPXimpact.

There is so much to talk about in transport to be honest (how geeky does that sound) and it is definitely another area that’s shot up the priority list with the new governments commitments . I’ll probably talk quite a lot about it in the coming weeks, as well as an inaugural intro to it in the context of our emerging Transport Practice within our cluster. With emerging Great British Railways ALB in nascency it feels like a real opportunity to reimagine transport in the wider ecosystem of the economic growth needed in the coming years.

Can I teach you to suck eggs?

I wanted to go back to basics first and start with an area we don’t talk so much about in the context of digital and transport. We will get to important areas such as Demand management, Transition to Electric Vehicles, Open Data Requirements and Modal Shift to Active Transport soon, but I really want to start with transport planning as it so integral to the governments ambitions in relation to planning reform and accelerating housing delivery.

It is also a prime area for digital innovation (or at least turning the dial towards more modern approaches).

Before we get to the shiny stuff (which I will cover in the rest of the series) I think its probably good to go back to basics and refresh minds on some of the current complexities and challenges in the transport planning landscape and where opportunities may be lurking.

Current context

Transport planning in the United Kingdom is a complex and involves numerous organisations and individual actors with competing priorities and a web of interdependencies. It is a crucial element in shaping the country’s infrastructure and ensuring that the demands of its citizens can be met. Transport planning is not just about designing roads, railways, and public transit systems; it also encompasses broader societal and environmental goals such as reducing carbon emissions, improving public health, promoting economic growth and crucially delivering the much needed housing needed.

Although there are pockets of strong innovation in the sector, including cutting edge data science and AI, this is mainly in the demand management and maintenance space and not joined up at scale.

The foundations and plumbing have still been largely untouched by modern approaches and many aspects of how we approach transport planning (including structures, process and data) however, are still strongly rooted in 20th century legacy practices, as are the organisations who are either responsible for designing, delivering and maintaining the infrastructure or part of the wider supply chain ecosystem.

Organisations Responsible for Transport Planning in the UK

A recap…

Transport planning in the UK is governed by a range of organisations at both the national and local levels. These organisations are required to work together, often in overlapping capacities, to develop, implement, and manage transport strategies and infrastructure projects.

- Department for Transport (DfT): The DfT is the central government body responsible for setting national transport policies and strategies. It oversees the planning and delivery of major transport infrastructure projects, such as the construction of motorways, rail networks, and ports. The DfT also allocates funding to local authorities and transport bodies, ensuring that national priorities are reflected in regional and local transport plans.

- Highways England (National Highways): Highways England is a government-owned company responsible for managing the strategic road network (SRN) in England, which includes motorways and major A roads. It plays a critical role in planning, maintaining, and improving the road network to ensure safe and efficient movement of people and goods across the country.

- Network Rail: Network Rail owns, operates, and develops the UK’s railway infrastructure. It is responsible for maintaining and enhancing the rail network, ensuring that it meets the needs of passengers and freight operators. Network Rail works closely with train operating companies, the DfT, and other stakeholders. (As a point of note, it will be interesting to see how the new GBR company sits and is aligned within this ecosystem as private operator contracts are gradually taken back in).

- Transport for London (TfL): TfL is the local government body responsible for managing the transport system in Greater London. This includes the London Underground, buses, trams, and the strategic road network within the city.

- Top Tier Local Authorities (Unitaries, Counties and Mets): Local authorities are responsible for developing and implementing Local Transport Plans (LTPs), which outline transport strategies for their respective areas. They manage local roads, public transport services, and active travel initiatives such as cycling and walking.

- Combined Authorities and Transport Authorities: Combined authorities are formed when two or more local authorities collaborate to create a single body responsible for certain functions, including transport planning. These authorities, such as Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM) and the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA), have devolved powers that allow them to plan and deliver transport projects at a regional level. This can enable a more coordinated approach to transport planning, particularly in metropolitan areas.

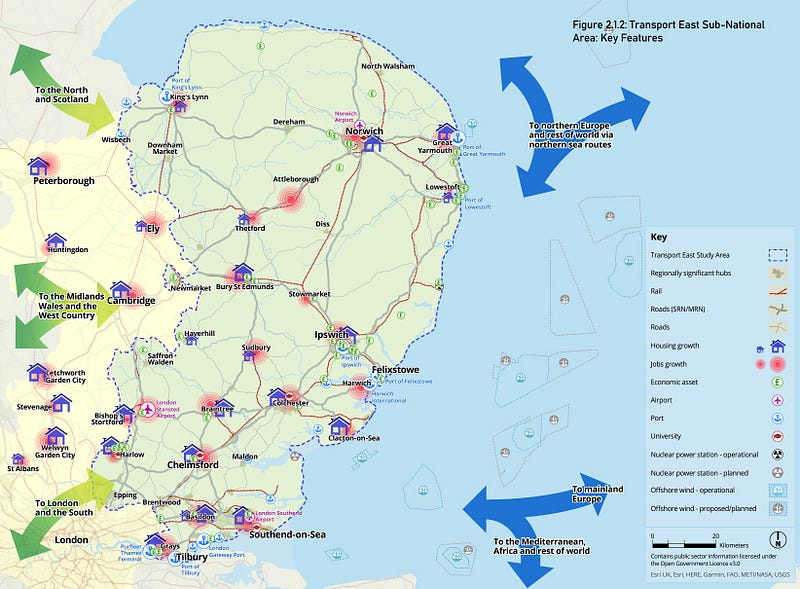

- Sub-national Transport Bodies (STBs): STBs, such as Transport for the North (TfN) and Midlands Connect, are regional partnerships that bring together local authorities, combined authorities, and other stakeholders to develop and implement strategic transport plans. STBs aim to address transport challenges that cross local authority boundaries and require a regional or national approach.

Demand Challenges

This needs a whole blog but the current lack of open data, joined up and sequenced statutory planning documents and industrial strategy data is a major area to address which could unlock much faster and more effective economic growth and development

Accurately predicting transport needs is super challenging and stems from a variety of factors, including population growth, economic changes, technological advancements, and environmental considerations.

- Population Growth and Demographic Changes: The UK’s population is expected to continue growing, particularly in urban areas, placing increased pressure on transport networks. However, predicting the exact rate and location of this growth is challenging and currently data is not collected, managed and used to best effect to aid more accuracy here. Changes in demographic patterns, such as aging populations or migration trends, further complicate this.

- Economic Volatility: Economic factors, such as fluctuations in employment rates, income levels, and industrial activity, significantly influence transport demand. For example, as we have seen as a result of a combination of negative economic factors catalysed by Brexit and COVID-19 (BROVID?— I might coin that) economic downturns lead to reduced travel as people cut back on commuting and discretionary trips, while economic booms can result in increased transport needs.

- Technological Advancements: The rise of electric vehicles, autonomous transport systems, and ride-sharing platforms could dramatically alter transport patterns. However, the adoption rates of these technologies are difficult to predict, making it challenging for planners to design infrastructure that will remain relevant in the long term.

- Decarbonisation and Sustainability Considerations: The UK government has committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, which has significant implications for transport planning. Planners must balance the need for new infrastructure with the imperative to reduce carbon emissions and protect natural environments. This often involves making trade-offs between short-term transport needs and long-term sustainability goals

- Behavioural Changes Post-COVID-19: The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on transport patterns, with many people adopting remote working, reducing travel, and shifting to active modes of transport like cycling and walking. While some of these changes may be temporary, others could represent long-term shifts in behaviour, making it difficult to predict future transport demand.

The Strategy and Policy Ecosystem

This list is limited (or we will have a book not a blog!) but there are many more that are entwined in the transport planning ecosystem which is often a key coordination challenge. We will try and look at these in more detail when we look at the opportunities for data alignment.

- Local Transport Plans (LTPs): LTPs are strategic documents developed by local authorities that outline the transport policies and priorities for a specific area, typically over a 15–20 year period. LTPs address various transport modes, including road, rail, public transit, and active travel, and set out plans for improving connectivity, reducing congestion, and promoting sustainable transport. LTPs are closely linked to local economic, social, and environmental objectives and must align with broader regional and national transport strategies.

- Local Plans: Local Plans are statutory documents prepared by local planning authorities that set out the spatial vision for development in a specific area, including housing, employment, and infrastructure. These plans typically cover a 15-year period and provide the framework for land use decisions, including where new housing, commercial developments, and transport infrastructure should be located. Local Plans are required to be consistent with national planning policy, but they must also reflect local priorities and needs.

- Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs): NSIPs are large-scale infrastructure projects deemed to be of national importance, such as major road schemes, railways, airports, and energy projects. These projects are subject to a streamlined planning process under the Planning Act 2008, which allows for faster decision-making compared to standard planning procedures. NSIPs are typically led by central government or major infrastructure providers, with input from local authorities and other stakeholders.

The Interrelationship:

LTPs, Local Plans, and NSIPs are interrelated, but they operate at different levels of planning, they are required to ‘talk to each other’ but this is currently very analogue and not at the level of detail and granularity required to take a proper systems approach (ergo proper integrated planning). I’ll talk about this in the next blog as sequencing of built infrastructure is so crucial and could be done sooooooooo much better with modern approaches and open data.

LTPs and Local Plans are closely linked, as transport infrastructure is a key determinant of land use patterns and vice versa. In terms of costs the delivery of housing is a key factor in development economics and could/should/sometimes does pay in lieu for a large percentage of transport infrastructure costs given the value capture of allocating land for housing and jobs.World Bank and City Resilience Programme Investment In Infrastructure

NSIPs, on the other hand, operate at a national or regional scale and do not always align perfectly with local priorities. However, they have significant implications for local transport and land use planning. This has been a growing challenge in recent years especially with a strategic infrastructure debt in areas like water and energy, and the need to accelerate the delivery of renewable infrastructure. The new emerging NPPF consultation articulates this and is an opportunity to think about the alignment and sequencing of NSIPs more effectively to unlock development.

A Nod To Devolution

More to come here as the year goes on but this is the general starting point

The increase devolving of powers to regional and local authorities in the UK, particularly in the area of transport planning can only be a good thing for alignment and sequencing of transport infrastructure which delivers to local needs. Big opportunities for innovation here and to the credit of many combined authorities this has already been moving forward at pace. My strong opinion here is that AGAIN, data and evidence flows between organisations and strategic and local policy will be paramount in improving insight led integrated planning. Some of the benefits of devolved powers are below but could definitely be expanded on with any forthcoming legislation changes;

- Greater Local Accountability and Flexibility: Devolved powers give local and regional authorities greater control over transport planning decisions, allowing them to tailor infrastructure projects to the specific needs and priorities of their areas. This increased flexibility can lead to more effective integration of transport and housing, as local authorities are better positioned to coordinate the timing and sequencing of these developments. Additionally, greater local accountability can ensure that transport and housing projects reflect the preferences of local communities, leading to higher levels of public support and less opposition.

- Improved Coordination Across Regional Boundaries: Combined authorities and STBs with devolved powers are better equipped to address transport challenges that cross local authority boundaries. This is particularly important in metropolitan areas where transport networks and housing markets often span multiple jurisdictions. By coordinating transport and housing planning at a regional level, these bodies can develop more coherent and integrated strategies that promote sustainable growth and reduce regional disparities.

- Enhanced Funding Opportunities: Devolution often comes with greater control over funding streams, allowing regional and local authorities to pool resources and invest in transport infrastructure that supports housing development. This can help overcome the funding challenges associated with aligning transport and housing projects, as devolved authorities can prioritise spending based on local needs and opportunities. For example, a combined authority with control over both transport and housing budgets could allocate funds to a new public transit line that opens up land for housing development, creating a virtuous cycle of investment and growth.

- Innovation and Experimentation: Devolved powers enable local and regional authorities to experiment with new approaches to transport and housing planning. For instance, they might pilot innovative funding mechanisms such as land value capture or explore new forms of public-private partnerships that leverage private investment for transport infrastructure. These experiments can generate valuable insights and best practices that can be scaled up or adapted in other regions.

- Stronger Alignment with Local Economic Strategies: Devolved authorities often have responsibility for economic development in their areas, allowing them to align transport and housing planning with broader economic strategies. For example, a combined authority might develop a transport plan that supports the growth of key economic sectors, such as technology or manufacturing, by improving connectivity to business hubs and ensuring that affordable housing is available nearby. This holistic approach can drive economic growth while also addressing social and environmental objectives.

What’s up next

So why all the geeky explainers you may ask, what’s coming next.

In the next blog I want to talk a little about the sequencing of housing and transport infrastructure and the opportunities for digital and data to really improve this and accelerate coordinated delivery. (you see where I’m going). Also connectivity and decarbonisation will need airing so watch this space for more integrated planning fun…